CRA Partnership FAQ

The Opportunity

Households with an individual with a disability have lower incomes and are more likely to be “unbanked,” meaning that no one in the household has a checking or savings account.[i] Unbanked individuals report that they are often hindered from using banking services by required minimum daily checking balances, poor credit, and fewer bank branches in some communities. As a result, unbanked individuals are more susceptible to predatory lending practices.[ii] Being “banked” is a critical component of financial capability, however, people with disabilities are less likely to access traditional banking services. [iii] [iv]

A 1977 federal law called the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) encourages banks to make investments to benefit low- and moderate-income individuals and neighborhoods, including workforce development-related activities for people with disabilities. [v] CRA activities can take many forms, from the development of financial services career pathways to financial education conducted by bank employees. [vi]

We developed this FAQ for workforce development boards and their staff members, community colleges, and others who provide workforce services. The FAQ provides answers to questions about workforce system–bank partnerships listed below.

FAQs

- What is the Community Reinvestment Act?

- What kinds of activities can banks engage in with workforce systems to support their CRA requirements and increase career success for individuals?

- Why focus on people with disabilities?

- What are some examples of partnerships between the workforce system and banks?

- What financial education benefits are possible under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act?

- What additional resources can facilitate understanding of and access to the benefits of the Community Reinvestment Act?

What is the Community Reinvestment Act?

The CRA is a 1977 law that sought to leverage the financial resources of private sector institutions to assist with community development. Banks receive CRA credit for participating in and funding activities in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods in their communities. The CRA defines a low-income community as a community with a median family income that is less than 50% of the area’s median income. [vii] A moderate-income community has a median family income that is at least 50% but less than 80% of the area’s median income. [viii]

To receive CRA credit for community development, a bank must have at least one of the following as its primary purpose: [ix]

- Community services targeted to individuals who have a low to moderate income;

- Activities that promote economic development, such as job training or financial education;

- Activities that revitalize or stabilize low- and moderate-income communities; or

- Initiatives that create or sustain affordable housing.

The CRA’s requirements apply to all banks, depending on the size of the institution. Credit unions do not have any requirements under the CRA, but they can be partners in financial education work.

What kinds of activities can banks engage in with workforce systems to support their CRA requirements and increase career success for individuals?

Banks can engage in a variety of activities with workforce systems to increase career success and financial security for people with disabilities, while supporting and meeting CRA requirements. [x] Among many other opportunities, these include:

- Teaching financial education, delivering the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Money Smart program, or offering financial counseling in workforce development programs;

- Providing donations to workforce development programs designed to improve employment opportunities for low- to moderate-income individuals with disabilities;

- Providing financial capability training to individuals with disabilities;

- Providing volunteer service with nonprofits to provide income tax assistance for low- to moderate-income individuals;

- Serving on workforce boards; or

- Helping to establish pipelines of talent to meet the needs of the financial services sector through apprenticeship or other work-based learning.

Why focus on people with disabilities?

Indicators such as national employment rates, unemployment rates, and the banking/lending practices of people with disabilities signal entrenched structural and other challenges that hinder achievement of economic self-sufficiency. For example, according to an analysis of findings from the 2017 FDIC national survey, people with disabilities have significantly lower rates of employment and higher rates of unemployment than individuals without disabilities.[xi]

Exhibit 1: Employment Data [xii]

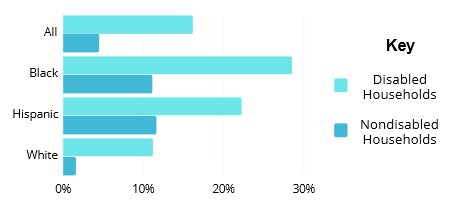

Moreover, working-age households that include a householder [xiii] with a disability are much less likely to engage with financial institutions.

Exhibit 2: Unbanked Working Age Households (2019)[xiv]

What are some examples of partnerships between the workforce system and banks?

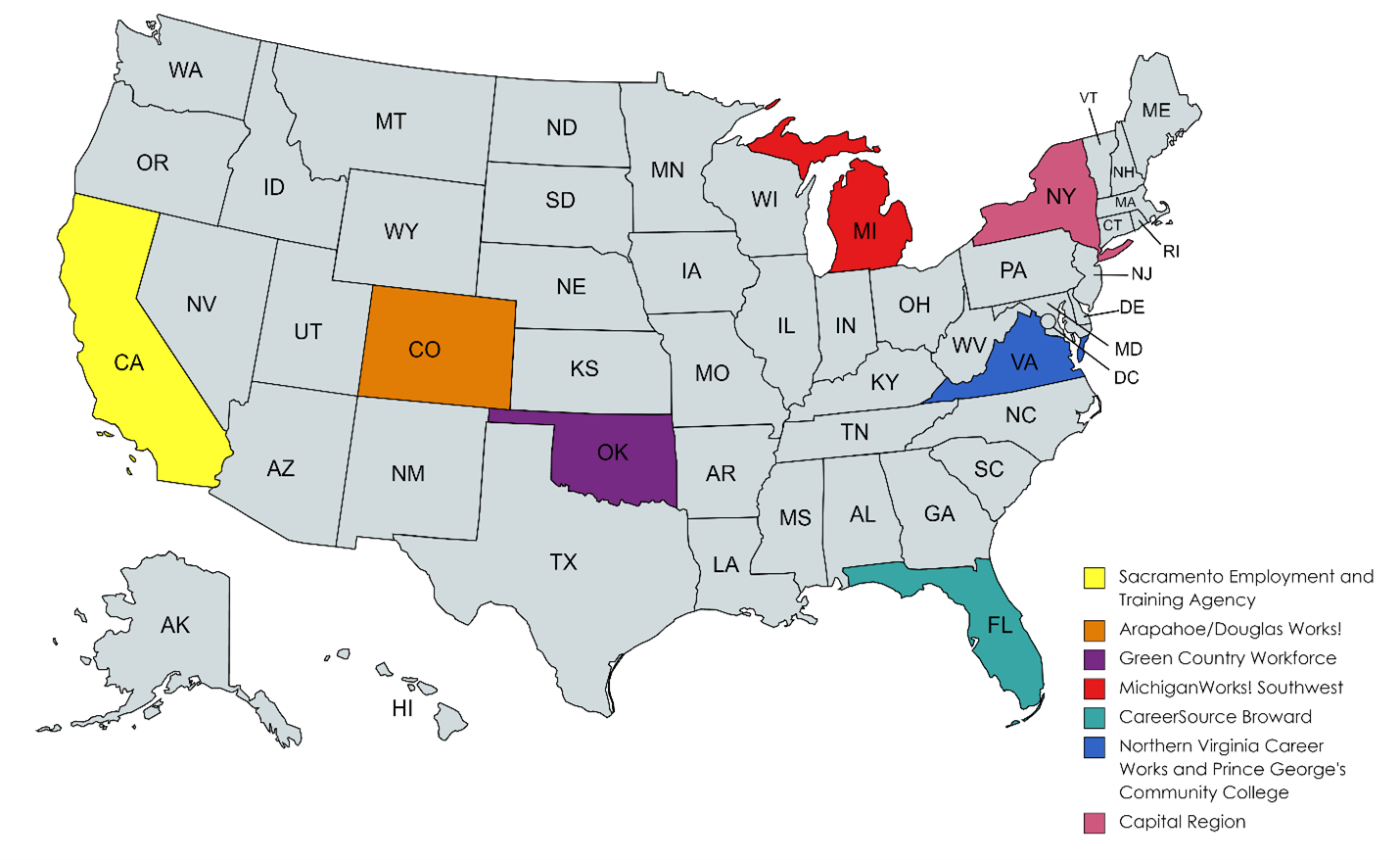

Below, we provide descriptions of seven workforce–bank partnerships in California, Colorado, Oklahoma, Michigan, Florida, Virginia, and New York.

California Capital Financial Development Corporation and Sacramento Employment and Training Agency (Sacramento, California)

The Sacramento Employment and Training Agency (SETA) developed a partnership with the California Capital Financial Development Corporation. As a result of this partnership, job seekers can access the following financial capability services through the workforce system:

- financial education;

- financial resources;

- financial counseling;

- financial assistance for entrepreneurs; and

- a Financial Empowerment Center (FEC).

In addition, the City of Sacramento established a FEC through the Bank On model. Bank On provides unbanked and underbanked individuals and families with asset building, banking access, consumer financial protection, and financial education and counseling. Financial Empowerment Centers offer professional, one-on-one financial counseling for local residents. Trained counselors help individuals pay down debt, increase savings, establish and build credit, access safe and affordable banking products, and build assets for long-term financial health. The city has integrated the FEC work with its overall strategy for building economic opportunities. Using prior funding, the International Rescue Committee, a local community-based organization, provided training through the FEC, and one of the team members from the workforce system became certified as an FEC instructor/coach.

Multiple Banks and Arapahoe/Douglas Works! (Denver, Colorado area)

The workforce system in Arapahoe and Douglas Counties, Colorado, partnered with Goodwill Industries of Denver in their BankWork$® program. BankWork$® provides young adults with training for entry-level positions in banking as well as work experience, coaching, and placement into careers in the financial industry. Wells Fargo and Bank of America support this workforce development approach nationally, and the Colorado Bankers Association endorses it. The following local partner banks also participate: Academy Bank, Bank of America, Bank of Denver, Bank of the West, Citywide Banks, KeyBank, U.S. Bank, Vectra Bank, and Young Americans Bank.

The BankWork$® model is a service and investment partnership between banks and the workforce system.

Multiple Banks and Green Country Workforce (Tulsa, Oklahoma)

The workforce board in Tulsa partnered with multiple banks through two of its programs: Career Advancement Program Tulsa and Tulsa Community WorkAdvance. Both programs have established workforce preparation and training activities focused on multiple career pathways and the career enhancement of low- and moderate-income individuals.

In addition, the City of Tulsa and Goodwill Industries support a FEC following the Bank On model. The Tulsa FEC provides resources and support to enhance participants’ personal financial capabilities, with an emphasis on training and career preparation and placement. Activities include workshops on financial capability, financial coaching, and access to financial services and supports. This combination of strategies has demonstrated a strong impact for targeted populations in Tulsa.

Multiple Banks and MichiganWorks! Southwest (Kalamazoo, Michigan)

Youth Opportunities Unlimited (YOU) — a division of Kalamazoo Regional Educational Service Agency (KRESA), the WIOA youth provider for MichiganWorks! Southwest — has developed partnerships with banks through KRESA’s new Career Awareness and Exploration team. This team established the FinLit (Financial Literacy) Fanatics Committee, consisting of a variety of banks, credit unions, and career coaches focused on providing financial education experiences to K-12 students.

The FinLit program uses a two-generation approach to support financial stability. This program pairs youth participants with a known adult (e.g., parent, mentor, guardian) and together they participate in workshops on job seeking, financial empowerment, and educational opportunities.

Bank of America with CareerSource Broward (Fort Lauderdale, Florida)

Since 2017, CareerSource Broward has worked closely with Bank of America. The bank funds summer work experience and financial capability training for 16- to 18-year-old youth in low- and moderate-income communities.

The workforce system also placed Bank of America’s “Better Money Habits” curriculum on computers in their American Job Center to make the financial capability training available as a career service to all job seekers.

SunTrust Bank with Northern Virginia Career Works and Prince George’s Community College (Virginia and Maryland)

In Virginia and Maryland, SunTrust Bank funded the creation of FECs that are designed to increase the financial capabilities of low- and moderate-income individuals. SunTrust provided grants through the United Way. The United Way then partnered with Virginia Career Works-Northern Region (a local workforce development board) and Prince George’s Community College (Largo, Maryland) to establish an FEC at an American Job Center and another on a college campus.

The FECs’ services include one-on-one financial coaching; small business coaching; workshops to address specific financial activities such as banking, saving, and taxes; and tax preparation in partnership with the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) Volunteer Income Tax Assistance program. Co-locating the FEC at an American Job Center and on a college campus allows for a more comprehensive approach to serving customers. The FECs pivoted to offer virtual services when the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Multiple Banks and Albany-Rensselaer-Schenectady County–Capital Region (Albany, New York)

Since 2001, the Creating Assets, Savings, and Hope (CA$H) Coalition has brought together banks and community-based agencies, including the workforce development board in Albany, New York, to provide programs that increase the financial capabilities of people with disabilities and others in the low- and moderate-income population. The Cities for Financial Empowerment Coalition spearheaded the development of the CA$H Coalition; Wildwood, an area nonprofit agency that is a part of the workforce system, leads it.

Known more widely as Bank On, the effort engages job seekers, especially people with disabilities, in the following activities and programs:

- financial capability workshops, where volunteers from banks and credit unions join other professionals to provide training;

- FECs, where staff from financial institutions volunteer and donate resources and expertise, including strategies for accessing bank and credit union services;

- financial-wellness coaching, where financial institutions offer one-on-one coaching in their own facilities upon referral; and

- volunteer income tax preparation, where volunteers from the community, including bank employees, with some funding support from the IRS, help people complete their tax returns.

Bank and workforce partners are developing financial industry career paths and will ensure that qualified job seekers with disabilities will be aware of, and available to, enter this pipeline.

What financial education benefits are possible under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act?

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) supports the provision of financial education activities for adults and youth and includes specific language intended to improve outcomes for individuals with disabilities and individuals with multiple challenges to employment. [xv] These provisions promote financial empowerment, enabling job seekers to increase their economic self-sufficiency and to participate in their communities. Promising career pathways programs also incorporate financial capability training to help people with disabilities successfully manage their finances once they obtain employment.

In WIOA Title I Adult Programs, adult job seekers can participate in financial education activities as appropriate, based on their Individual Employment Plans (IEPs). An IEP outlines the appropriate combination of services a job seeker will receive to meet their employment goals and objectives. The assistance can include skills development to attain career objectives, individual and group counseling, short-term prevocational services, communication and interviewing skills, internships and work experience, as well as financial education services.

The WIOA Title I Youth Program includes financial literacy education as one of 14 services that must be available to youth participants. WIOA youth financial education provides individuals with the skills and knowledge they need to achieve long-term financial stability. As listed in section 129 of WIOA, these skills and knowledge include making and using budgets, saving, planning effectively for education and retirement, and using credit as well as financial products and services effectively.

What additional resources can facilitate understanding of and access to the benefits of the Community Reinvestment Act?

Center for Disability-Inclusive Community Development (CDICD) nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/disability-inclusive-community-development

The CDICD works to improve the financial health and well-being of low- and moderate-income individuals with disabilities and their families by increasing awareness and usage of the opportunities and resources available under the CRA.

In its webinar, Workforce Development and Meeting Obligations Under CRA, the CDICD explores how the CRA can support workforce development outcomes for people with disabilities. The webinar presents an overview of the CRA and its connection to workforce development. The resource also includes a discussion of how partnerships can be developed and strengthened from the perspective of both the organization serving people with disabilities and the bank partner.

“Hands On Banking” Quick-Reference Guides and Disability Supplemental Guides

nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/resources/hob-qrg-and-supplemental-guides

Hands On Banking quick-reference guides provide information and resources that address 15 different barriers that individuals with disabilities may experience. The disability supplemental guides cover disability sensitivity and information to complement the Hands On Banking instructor guides for adults, young adults, and entrepreneurs. Subjects include employment, money management, protected savings, work supports and other financial capability topics relevant to individuals with disabilities. These guides also provide numerous tips, tools, resources and links to Hands On Banking materials.

Banks’ Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) Opportunities for Promoting Job Creation, Workforce Development, and Place-Based Investments

This report, published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia in October 2017, summarizes innovative activities from banks’ CRA performance evaluations in the areas of job creation, education, workforce development, transportation, and affordable housing. The document highlights real-world examples featuring banks who promoted economic growth and prosperity in their communities while receiving credit under the CRA.